While I was in art school and while I was teaching one of the more popular techniques employed by professors and teachers was something called the “group critique.” I’ve never liked them either as a student or as a professor and I actually think that “group crits” probably lead to more pretentious posturing, conflict and hurt feelings than any other behavior at art school. Here’s what they are and how to deal with them. (I’m also going to follow up with how to get give and get good criticism that’s useful.)

What is a “group critique.”

The group critique, aka group crit

in the classroom setting, usually consists of the students sitting in a circle

or roundtable while one student presents their work to the class.

The student is asked to present and explain their work to

the group and then the group is expected to provide thoughtful feedback. The presentation

is usually a 3-to-4-minute explanation using a lot of jargon or art speak to

explain what the goal of the work of art being presented was. After the

presentation, the other students in the class are invited to provide negative

and positive feedback about how successful the project was according to their

personal opinions. There are many variations on how this is conducted and in

general these kinds of presentations can lead to hurt feelings and alienation

as well as star worship and a popularity contest.

Part of the rationale for group critiques is for students to

learn how to speak effectively and communicate to an audience about their work

persuasively. Probably a better way to learn how to do this is to pay attention

in freshman English which teaches you a great writing format called the five-paragraph

essay. Also, take a creative writing course and write short

biographical stories about your experiences in the studio that you’ll be able

to use as artist statements and press pieces later. Go take a creative writing

class.

First of all, I think the most basic rule in any social

situation, classrooms, social media, a party, or even just hanging out with a

friend is to follow the adage, “if you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t

say anything at all.”

I understand that this sounds very simplistic but all one has to do is log into Facebook and see how much people love to take offense and argue in a social media setting to understand how unproductive and unconvincing arguing opposing points of view and just plain being nasty in a social setting can be.

My suggestion, for art school and social media interactions,

is to just be nice and try to avoid conflict where conflict is not necessary.

It’s always better to say nothing or to walk away from an argument rather than

to get into a feud with someone and have that become the precedent that will

govern the rest of your relationship with them. I’ve seen this happen time and

again in art school where jockeying for popularity and attempting to denigrate

someone or someone else’s work to make one feel better never works and in fact

can lead to long-term damage on a young artist's reputation.

When you’re in a “group crit” and you are the subject or

focus of criticism it’s best to respond by justifying or explaining why that

person is wrong in their judgment or criticism of your work.

Probably the best technique that I’ve seen when I’ve seen students confronted with overtly aggressive or negative criticism is for the person being criticized to just say,

“Thanks, I’ll think about that.”

“That’s great feedback, thank

you.”

“Thank you for your

observations, I’ll consider what you said.”

Or just saying, “thank you.”

And choosing not to reply beyond that.

This takes a lot of discipline because when one feels

insulted it’s a natural reaction to justify, argue or retaliate. Sometimes,

this also leads to attacks and negative divisive behavior even when the artist/student

who criticized you stands in the same spot and you choose to attack them, which

is equally a bad idea.

I’ve seen professors and teachers totally foster an

environment in which students are fighting for popularity and at each other’s

throats. The reasons why professors and teachers do this is often rooted in

their own treatment when they were in art school but sometimes, they just

rejoice in watching the drama and conflict unfold. Don’t fuel the sadistic

desires of people who enjoy conflict by participating in angry retaliation and

overt negative behavior. It won’t help you and it could hurt you in the long

run.

What do you do if you are expected to provide a critique in a group setting?

If it is possible and you are forced into saying something

say something positive about the student’s work such as complimenting one of

the formal aspects, line quality, color, composition, texture, perspective,

accuracy of drawing, or complement the content or iconography of the image.

You can say something nice about the content or the

meaning of the piece or say that it is a good fulfillment of the concept

that they had discussed.

Another possible compliment would be to discuss how

relevant the work of art is to the project, today’s world, a social issue.

However, sometimes professors will push students into conflict by insisting

that they say something about the work of art that needs to be improved or is

essentially a negative criticism. Here’s how to deal with that.

Again, it’s best to say as little as possible in a public

forum about someone else’s artwork, and to reserve any kind of criticism to a

private venue. Even if your professor is pushing for you to evaluate and

provide a negative comment about a fellow art students work it’s best to keep

it to a minimum and to keep it as factual as possible. For example, you could

use the elementary school teacher’s technique of the so-called “compliment

sandwich.” The complement sandwich consists of, compliment followed by a

palatable critique, followed by another compliment. Here’s an example,

“I like the composition in this

piece, perhaps the hand is a little too large proportionately, but I think the

content and meaning of your work is very powerful.”

Don’t go off on a long diatribe or a soliloquy about another person’s work of art because it just doesn’t feel good when someone does that and you’re up for critique in front of the classroom.

Why I’m against the use of the group critique in the

classroom.

I believe that the group critique is a sort of “Lord of the

Flies,” situation and always leads to people feeling slighted or having their

feelings hurt. At best it creates popular students who are clearly the rising

stars to follow at worst it creates scapegoats and victims in the classroom and

low self-esteem. It also creates an environment in which students learn how to

use buzzwords and phrases that essentially make them sound smart and in control

of the vocabulary but communicate even less.

I substituted group critiques with a much more labor-intensive

process in which I would write students individualized responses to their works

based on a rubric or criteria that I established before the project. Usually

when I was grading a work of art for student, I would provide several sentences

addressing the formal aspects of what they were learning, such as line, color,

composition, technique, texture, perspective, shading. I avoided using art

buzzwords or jargon. The second thing that I would provide would be an analysis

of the content or subject of their image and how effective it was in

communicating ideas. Again, I avoided a lot of heavy jargon however, I am

partial to the term “iconography.” Sometimes it was relevant, I would also

provide a sentence or two about how socially, politically, or emotionally

relevant the work was either to the student’s personal context or the world at

large.

So how do you get constructive criticism from other people while you’re in art school?

I have had a lot of good experiences getting constructive

criticism from professors, teachers, other art students, and friends by asking

them for it privately and also making sure that I ask only from people whose

art I respect and like. Sometimes

getting a private critique can feel much safer but can also hurt more because

this person is telling you something that you might need to hear. You have to

ask for criticism from people who have your best interest at heart and it takes

a lot of emotional intelligence to ask someone at to judge who really cares

about you and your development. Make sure it’s someone who makes good art.

Here are a couple of anecdotes about positive criticism

that I’ve received from artists who I respected.

John Stewart, University of Cincinnati 1993

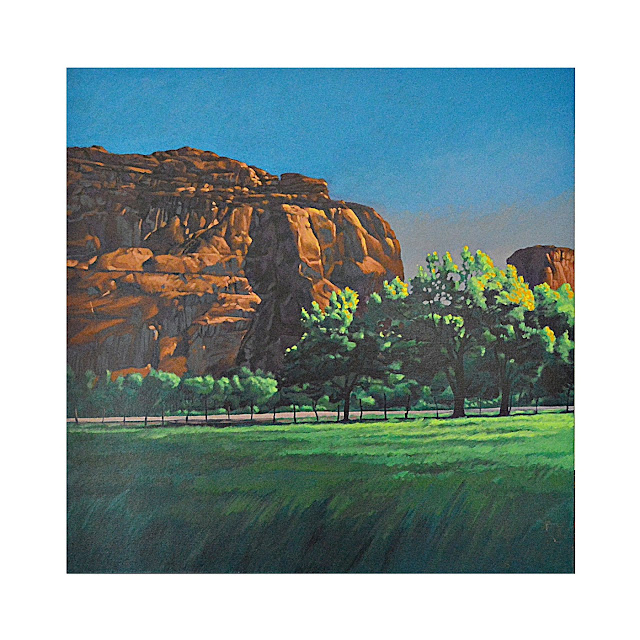

While I was studying painting at the University of Cincinnati, I had a professor named John Stewart who made a comment in a life painting class to me about color theory and that he could help me with that.

John had already done a presentation of his art to our MFA

class complete with slides and biographical information. He also had just had a

show at an art gallery in downtown Cincinnati that I had attended and so I was

familiar with his landscapes and his art in general. I also was taking a life

painting class with and saw how kind he was to the other students and how he

conducted himself. I respected his work, his work ethic, how we communicate

with other students, and how he communicated with me when providing me with on-the-spot

criticism in the life painting class. This is someone I knew that I could

trust. I waited after class several classes and help to clean up and chatted

him up to see if he would be interested in starting a relationship with me.

|

| John P. Stewart Oil on Canvas of a Canyonlands Landscape |

We arranged for him to come to my studio and John came in looked around, sat down, and took out a sketchbook that he used also as a notebook. He did not comment at all about the paintings on the walls or point out individual things in the paintings but instead started to talk to me about color theory and choices of pallets of color. He took some time and sketched out diagrams in his sketchbook to show me how color theory worked and then the next time I saw him he gave me a color chart and explained how I should use it. We would have biweekly meetings were he would come into my studio, often not looking at the work on the walls, but talk to me about things that he thought I need to know about color theory, suggested color combinations with oil paint, composition and anatomy. He also talked to me about how to behave professionally as well as introducing me to an art dealer who later on gave me a show. It was some of the most useful “criticism” I had ever received.

|

| Kenney Mencher, 45" × 35" mixed media on paper 2005 by David Tomb |

David Tomb San Francisco California

Another artist who I met 30 years ago while I was a graduate

student at Davis is an artist named David Tomb. David has looked at and

critiqued my work for at least 2 to 3 decades. I met him through a friend while

I was a graduate student studying art history at the University of California

Davis. I was a painter even though I was going through a two-year program for

an MA in art history. I visited his studio several times and even though I

really couldn’t afford it I bought one of his paintings and also attended

various shows he had in San Francisco. At the time that I was getting to know

him I didn’t really talk to him about the paintings I was making and never

asked him for criticism. He was just my friend whose work I thought was

phenomenal enough for me to buy.

Years later when I had already graduated from two masters’

programs and was teaching at Ohlone College in Fremont, David would invite me

to his studio to look at his work and we developed a relationship in which I

actually modeled for him for some drawings and paintings he was making. While

modeling for him we talked about art quite a bit and I picked his brains. After

a bit, I asked him if it would be all right if I were to bring by some

paintings for him to critique for me so that I could improve.

|

| Philippine Eagle, by David Tomb |

David’s critiques of my work were almost always overwhelmingly positive. However, that’s not to say that he didn’t make a lot of suggestions on how I could improve my paintings but he did it in such a seamless way using the “complement sandwich” that I talked about earlier in this essay. He would start by talking about how much he liked the content of the painting and in particular how much he liked my handling of the subject matter and what it meant to him. So, I was immediately put it ease and open to suggestions that he would make about the formal issues. His formal critiques of my paintings were thorough and very clear, and if it’s possible, very objective.

David would begin by talking about the edges of the figures

in the painting and where planes would meet. He would then go on to talk a

little bit about composition and paint texture. Sometimes he would address the

deficits in my anatomy, such as hands and the structure of the figures and make

suggestions as to where I might improve them. He rarely discussed color. Often,

he would talk about shading or chiaroscuro in the paintings often more in a

positive light.

What I’m suggesting in this story is that, first I respected

his work and even held him as kind of a hero for me as an artist. Second, he

was always kind and a kind of gentlemen in how he approached my work and even

when giving negative criticism offered solutions as to how to fix the problem.

This created trust because it wasn’t about him telling me with a great artist

he was or telling me that I wasn’t good enough he focused on how I could

improve my art. Over the years David also attempted to introduce me to gallery

directors and movers and shakers in the art world. By the way, even though he

attempted to pull me into his world which is a slightly more upscale kind of art

world I never really participated in the art world that caliber or level.

Something I’m actually not bitter about. In my mind David is just a different

kind of artist than I am.

__________________________________________________________

Afterword/Conclusion/Reaction

A bit of an ironic response happened after I shared this to a group that I administrate on Facebook. For me it is almost a perfect example of the ideas presented in this blog post.

No comments:

Post a Comment