For a full online text and a complete set of videos for $20 please visit:

http://art-and-art-history-academy.usefedora.com/

"Man is the measure?"

Women's roles during the Renaissance

TIZIANO Vecellio (Titian) The Venus of Urbino 1538 Oil on canvas, 119 x 165 cm

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italian Renaissance

In the background of Titian’s painting entitled "The Venus of Urbino" (1538) are two women looking inside or placing things inside a chest. This chest or cassone is most likely a dowry chest, in which case the women are then preparing the chest with gifts for the upcoming nuptials. Venus, the goddess of beauty, nude in the foreground, presides over the event, but there’s something wrong with this picture. Venus is really the Duke of Urbino’s courtesan (mistress) and the title of the painting is just a disguise to make a nearly pornographic portrait palatable. This kind of double meaning in a painting is common during the Renaissance especially in portrayals of women.

What is also interesting about this images is that the artist chose to juxtapose the eroticized female form with commodities or luxury items. By playing the textures and body of the female against expensive fabrics, fur, fruit, and dowery chest containing the family jewels and porcelain, the artist is also making the human female form another commodity which can be bought and sold. In this way, the wealth of the patron is also eroticized. This device is played off again and again throughout the history of art.

The cassone is a familiar object in the upper class Renaissance home. Provided by the bride’s family and kept throughout her life the chest is symbol of her marriage. The decorations on the chest are designed to educate the woman who owns it. The images that adorn cassoni relate familiar classical and biblical narratives concerning the lives of great women. For example, San Francisco’s "Legion of Honor" has a panel from a cassone by Jacopo del Sellaio that depicts the "Legend of Brutus and Portia," circa 1485. Both Plutarch (AD 46-119), a Greek historian, and Shakespeare (1554-1616) in his play "Julius Caesar," depict Portia as a strong and loyal wife. In Shakespeare’s "Julius Caesar," Portia exclaims, "Think you I am no stronger than my sex, Being so fathered and so husbanded?" (Act 2, i, 319-320) and stabs herself in the leg to prove to Brutus that she can bear any discomfort for him. After she learns of Brutus’ defeat, she kills herself by swallowing hot coals. Another cassone from the Louvre depicts the Old Testament story of Queen Esther and her self-sacrificing patriotic acts that saved the Jewish people. The subtext of these tales is not just loyalty but self-sacrificing loyalty in the face of adversity.

Titian's painting has been the subject of much observation. It's interesting that so much positive "press" has been associated with this image considering how much it has been vilified in the past. Mark Twain, in his biography Tramp Abroad, recorded his response to his encounter with the Titian painting:

http://art-and-art-history-academy.usefedora.com/

"Man is the measure?"

Women's roles during the Renaissance

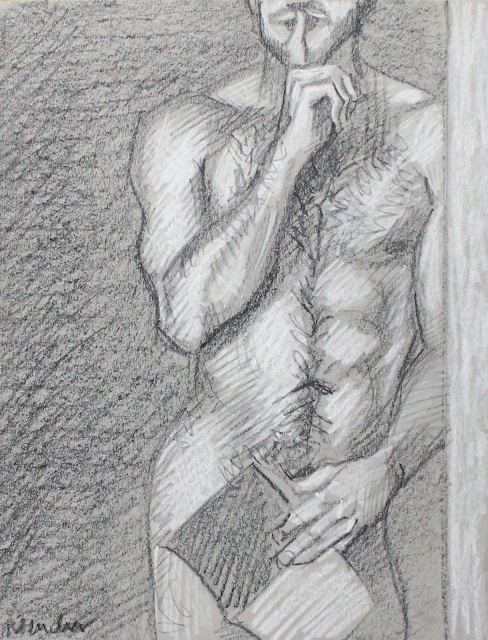

Hans Baldung Grien, Aristotle and Phyllis. 1503 pen and ink | Form: This is a simple sketch in pen and ink that was probably a prelimionary drawing for an engraving or a painting. The anatomy is rather stiff and less gestural than those of his contempoarry Italian counterparts.Space is created through a size scale relationship of foreground to background and a variation of marks in the nackground buildings indicates a use of atmospheric perspective. Grien uses cross contour lines (lines that literally follow the direction across the curves of the trunks) to indicate the texture of the tree and cross hatching to develop the value structure of the figures and their drapery in the foreground. These linear techniques would have been important for a printmaker to master. Iconography: The them of an "ill matched couple," which usually depicts a young and beautiful maiden in the company of an older man is a common them in Renaissance art of the North. In many images the younger woman has her hand on the purse of the older man but in this case the subject matter of the image is a young beautiful woman dressed in Renaissance clothing of the Northern style riding around or taming an older man. Images like this were meant to be a warning to men of the power of inappropriate passion and a warning against the sexual powers of young woman. Context: More specifically this relates to the story of Aristotle, the Greek philosopher and Phyllis, the wife of his pupil Alexander the Great. According to the Brittanica, "in late 343 or early 342 Aristotle, at about the age of 42, was invited by Philip II of Macedon to his capital at Pella to tutor his 13-year-old son, Alexander. As the leading intellectual figure in Greece, Aristotle was commissioned to prepare Alexander for his future role as a military leader. As it turned out, Alexander was to dominate the Greek world and defend it against the Persian Empire."This union of older philosopher master was the beginning of a nearly lifelong advisory position for Aristotle. Alexander respected the superior intellect of Aristotle in all things and felt that Aristotle represented the ideal intellectual who represented a total mastery of the intellectual over the physical self. (Remember the Apollonian Dionysian conflict?) Phyllis questioned Aristsotles absolute control and according to legend made a bet with Alexander that she could show him that passion was stronger than reason. She began to flirt with Aristotle. After inflaming Aristotle with lust, he began to beg for a sexual trist. Phyllis informed Alexander that she had the proof he sought and instructed Alexander to hide in the bushes and watch while she literally mad an "ass" out of Aristotle. In order to get what he wanted, Aristotle had to agree to do whatever Phyllis wanted. She instructed Aristotle to get down on all fours and allow her to ride him around the courtyard. |

BALDUNG GRIEN, Hans Aristotle and Phyllis 1513 Woodcut, 33 x 23,6 cm | Form: In this variation of the theme, the two figures are nude and the total environment is much more worked out. This image indicates a fairly good use of anatomy and perspective and shows more of a development of the mark making discussed in Grien's drawing. The development of the vocabulary of marks would have been important for Grien to be able to make a high quality engraving.Engraving Context: In the North, places like Germany, France and Holland, the art market was a bit different than in Italy. Although the Reformation did not officially begin until 1518, there were stirrings of it earlier than that. In Northern towns and cities, there was a different distrubution of wealth and probably a larger upper middle class than in Italy. In addition to these factors, the main patron for the arts was in Italy in the Churches of Rome, Padua and Florence. Since individuals could afford to buy work for smaller prices many artists sought out this different market. The print market allowed artists to sell multiple copies of the same images to a larger number of people and make as much money from it as the sale of one or two paintings. This also freed some of the artists from the typical more Catholic or overtly religious iconography of much of the art of the South and allowed them to explore other kinds of imagery and subjects. |

Hans Baldung Grien. Stupified Groom. (Bewitched Groom) 1544. Woodcut 13"x 7" State Museum of Berlin | Iconography: Stokstad describes the iconography of this image as a "moral lesson on the power of evil" but more than that, Stokstad discusses the use of images of witches in his images as an expression of evil. It is interesting that this is one of the roles that older, perhaps unattractive woman were accused of during the Renaissance and well into the 1800's. In some ways, the depiction of witches in the art of the Renaissance represents the anti-ideal for a woman. In this way, woman are still provided with a role model of what not to become. Form and Context: Woodcut is the technique of printing designs from planks of wood. . . It is one of the oldest methods of making prints from a relief surface, having been used in China to decorate textiles since the 5th century AD. In Europe, printing from wood blocks on textiles was known from the early 14th century, but it had little development until paper began to be manufactured in France and Germany at the end of the 14th century. . . In Bavaria, Austria, and Bohemia, religious images and playing cards were first made from wood blocks in the early 15th century, and the development of printing from movable type led to widespread use of woodcut illustrations in the Netherlands and in Italy. With the 16th century, black-line woodcut reached its greatest perfection with Albrecht Dürer and his followers Lucas Cranach and Hans Holbein. In the Netherlands Lucas van Leyden and in Italy Jacopo de' Barbari and Domenico Campagnola, who were, like Dürer, engravers on copper, also made woodcuts.As wood is a natural material, its structure varies enormously and this exercises a strong influence on the cutting. Wood blocks are cut plankwise. The woods most often used are pear, rose, pine, apple, and beech. The old masters preferred fine-grained hardwoods because they allow finer detail work than softwoods, but modern printmakers value the coarse grain of softwoods and often incorporate it into the design. |

TIZIANO Vecellio (Titian) The Venus of Urbino 1538 Oil on canvas, 119 x 165 cm

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italian Renaissance

In the background of Titian’s painting entitled "The Venus of Urbino" (1538) are two women looking inside or placing things inside a chest. This chest or cassone is most likely a dowry chest, in which case the women are then preparing the chest with gifts for the upcoming nuptials. Venus, the goddess of beauty, nude in the foreground, presides over the event, but there’s something wrong with this picture. Venus is really the Duke of Urbino’s courtesan (mistress) and the title of the painting is just a disguise to make a nearly pornographic portrait palatable. This kind of double meaning in a painting is common during the Renaissance especially in portrayals of women.

What is also interesting about this images is that the artist chose to juxtapose the eroticized female form with commodities or luxury items. By playing the textures and body of the female against expensive fabrics, fur, fruit, and dowery chest containing the family jewels and porcelain, the artist is also making the human female form another commodity which can be bought and sold. In this way, the wealth of the patron is also eroticized. This device is played off again and again throughout the history of art.

The cassone is a familiar object in the upper class Renaissance home. Provided by the bride’s family and kept throughout her life the chest is symbol of her marriage. The decorations on the chest are designed to educate the woman who owns it. The images that adorn cassoni relate familiar classical and biblical narratives concerning the lives of great women. For example, San Francisco’s "Legion of Honor" has a panel from a cassone by Jacopo del Sellaio that depicts the "Legend of Brutus and Portia," circa 1485. Both Plutarch (AD 46-119), a Greek historian, and Shakespeare (1554-1616) in his play "Julius Caesar," depict Portia as a strong and loyal wife. In Shakespeare’s "Julius Caesar," Portia exclaims, "Think you I am no stronger than my sex, Being so fathered and so husbanded?" (Act 2, i, 319-320) and stabs herself in the leg to prove to Brutus that she can bear any discomfort for him. After she learns of Brutus’ defeat, she kills herself by swallowing hot coals. Another cassone from the Louvre depicts the Old Testament story of Queen Esther and her self-sacrificing patriotic acts that saved the Jewish people. The subtext of these tales is not just loyalty but self-sacrificing loyalty in the face of adversity.

Titian's painting has been the subject of much observation. It's interesting that so much positive "press" has been associated with this image considering how much it has been vilified in the past. Mark Twain, in his biography Tramp Abroad, recorded his response to his encounter with the Titian painting:

Now that you know how Twain felt about this work. This poem by Browning discusses a similar painting. It is used by the narrator of the poem as a point of departure to discuss how he feels about his last wife and how he feels women should behave. As you read it, try to relate the painting above to it.You enter [the Uffizi] and proceed to that most-visited little gallery that exists in the world --the Tribune-- and there, against the wall, without obstructing rap or leaf, you may look your fill upon the foulest, the vilest, the obscenest picture the world possesses -- Titian's Venus. It isn't that she is naked and stretched out on a bed --no, it is the attitude of one of her arms and hand. If I ventured to describe that attitude there would be a fine howl --but there the Venus lies for anybody to gloat over that wants to --and there she has a right to lie, for she is a work of art, and art has its privileges. I saw a young girl stealing furtive glances at her; I saw young men gazing long and absorbedly at her, I saw aged infirm men hang upon her charms with a pathetic interest. How I should like to describe her --just to see what a holy indignation I could stir up in the world...yet the world is willing to let its sons and its daughters and itself look at Titian's beast, but won't stand a description of it in words....There are pictures of nude women which suggest no impure thought -- I am well aware of that. I am not railing at such. What I am trying to emphasize is the fact that Titian's Venus is very far from being one of that sort. Without any question it was painted for a bagnio and it was probably refused because it was a trifle too strong. In truth, it is a trifle too strong for any place but a public art gallery.

| "My Last Duchess" - Robert Browning - 1842 1 That's my last Duchess painted on the wall, 2 Looking as if she were alive. I call 3 That piece a wonder, now; Frà Pandolf's hands 4 Worked busily a day, and there she stands. 5 Will't please you sit and look at her? I said 6 "Frà Pandolf" by design, for never read 7 Strangers like you that pictured countenance, 8 The depth and passion of its earnest glance, 9 But to myself they turned (since none puts by 10 The curtain I have drawn for you, but I) 11 And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst, 12 How such a glance came there; so, not the first 13 Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, 'twas not 14 Her husband's presence only, called that spot 15 Of joy into the Duchess' cheek; perhaps 16 Fra Pandolf chanced to say, "Her mantle laps 17 Over my lady's wrist too much," or "Paint 18 Must never hope to reproduce the faint 19 Half-flush that dies along her throat." Such stuff 20 Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough 21 For calling up that spot of joy. She had 22 A heart - how shall I say? - too soon made glad, 23 Too easily impressed; she liked whate'er 24 She looked on, and her looks went everywhere. 25 Sir, 'twas all one! My favor at her breast, 26 The dropping of the daylight in the West, 27 The bough of cherries some officious fool | 28 Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule 29 She rode with round the terrace - all and each 30 Would draw from her alike the approving speech, 31 Or blush, at least. She thanked men, - good! but thanked 32 Somehow - I know not how - as if she ranked 33 My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name 34 With anybody's gift. Who'd stoop to blame 35 This sort of trifling? Even had you skill 36 In speech - which I have not - to make your will 37 Quite clear to such an one, and say "Just this 38 Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss, 39 Or there exceed the mark" - and if she let 40 Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set 41 Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse - 42 E'en then would be some stooping; and I choose 43 Never to stoop. Oh, sir, she smiled, no doubt, 44 Whene'er I passed her; but who passed without 45 Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands; 46 Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands 47 As if alive. Will't please you rise? We'll meet 48 The company below, then. I repeat, 49 The Count your master's known munificence 50 Is ample warrant that no just pretense 51 Of mine for dowry will be disallowed; 52 Though his fair daughter's self, as I avowed 53 At starting, is my object. Nay, we'll go 54 Together down, sir. Notice Neptune, though, 55 Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity, 56 Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me. |